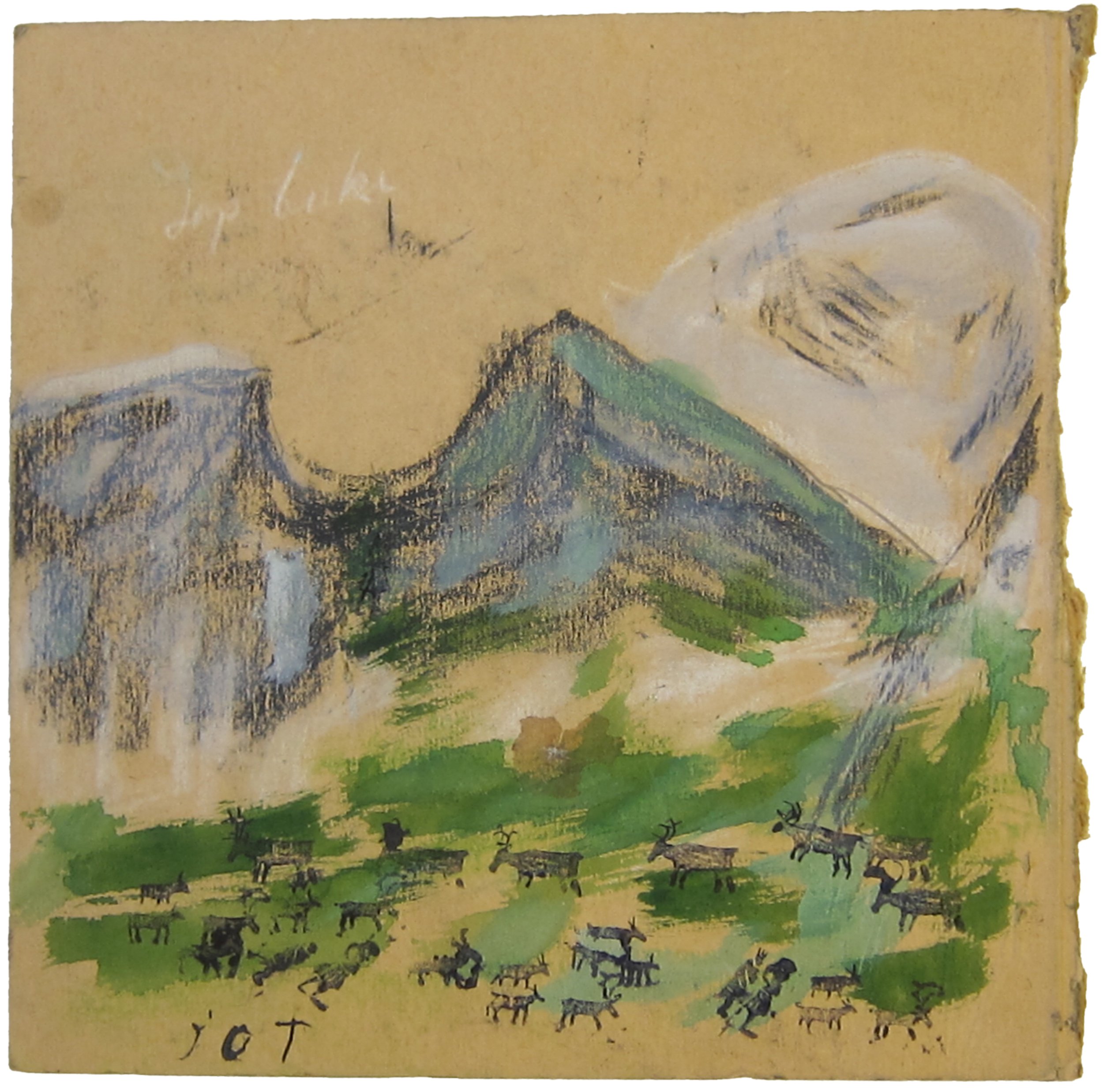

Johan Turi. Lap Luki (Čuonjávággi/The Lapponian Gate). Date unknown. Mixed technique on cardboard (pastel, gouache and Indian ink, or similar). 20 x 21 cm (irregular). The Johan Turi Archives. Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. LA 659, No. 10, Box J1:1. Photo: Svein Aamold.

The spectacular motif of the U-shaped valley Čuonjávággi/Lapporten (North Sámi: “Goose Valley”; Swedish: “The Lapponian Gate”) was popular among visiting tourists as well as artists. Johan Turi’s Lap Luki [Čuonjávággi/The Lapponian Gate] presents an inhabited nature as he knew it, in a formally simplified, somewhat coarse style. He used wooden stamps which he had carved to represent multiple equal shapes, such as humans, reindeer, or trees, thus also saving the effort of drawing each of them individually. Also characteristic of his paintings, both here and elsewhere, are strong hues, clashing complementary colours, avoidance of traditional harmonies, and an overall “raw” and expressive visual quality. The surface qualities of opaque versus transparent, broad outlines, and visible tracks of the executing movements of his hand are heightened by his changing use of mixed techniques, such as pastel, gouache, watercolour, Indian ink, and pencil.

We know little about what Turi might have learned about drawing and painting. According to Ernst Manker, the Swedish artist Edith Maria von Knaffl-Granström (1884–1956) gave him lessons on watercolour techniques, but we do not know when. Turi’s economy did not permit him to buy and use proper equipment as a painter. He worked on whatever paper or carton he could get hold of, sometimes, as here, a torn-off part of a cardboard box for clothes or shoes. He left the rough right side as if it has just been ripped off, giving an impression of something raw, or, perhaps, something unfinished, underway. Their commercial value was insignificant if compared to many of the Swedish landscape painters’ success in the art market.

Importantly, however, Turi did not quite adjust to the genre of landscape painting. Lap Luki shows simplified shapes of the sky, clouds, and terrain, with herders and their animals occupying much of its lower areas. The stark contrast between the green fertile areas and the hovering bare mountains is telling. For Turi, nature gives and takes; it is the home of the Sámi herders, but also delimits their lives. High up in the mountains, conditions can be dangerous. The partly transparent white colour surrounding the summits refers, perhaps, to drifting haze.

The visiting painters at the time generally represented an idea of a “pure”, uninhabited landscape, as if untouched by human beings. Theirs was a neo-Romantic conception of the mountain areas of Sápmi as wild and virginal terra nullius in which civilization has not (yet) made its mark. The great difference to the Swedish artists, then, is Turi’s deep knowledge and understanding of the conditions of nature in this region, its changing seasons, its flora and fauna, and the lives, works, customs, knowledge, and belief systems of the Sámi. Turi’s interpretation stands as a necessary corrective on behalf of the Sámi.

Essay by Svein Aamold

Further reading

Svein Aamold. 2023. ‘Johan Turi’s Ecology’. Interventions, 25(7), 878–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2023.2169625