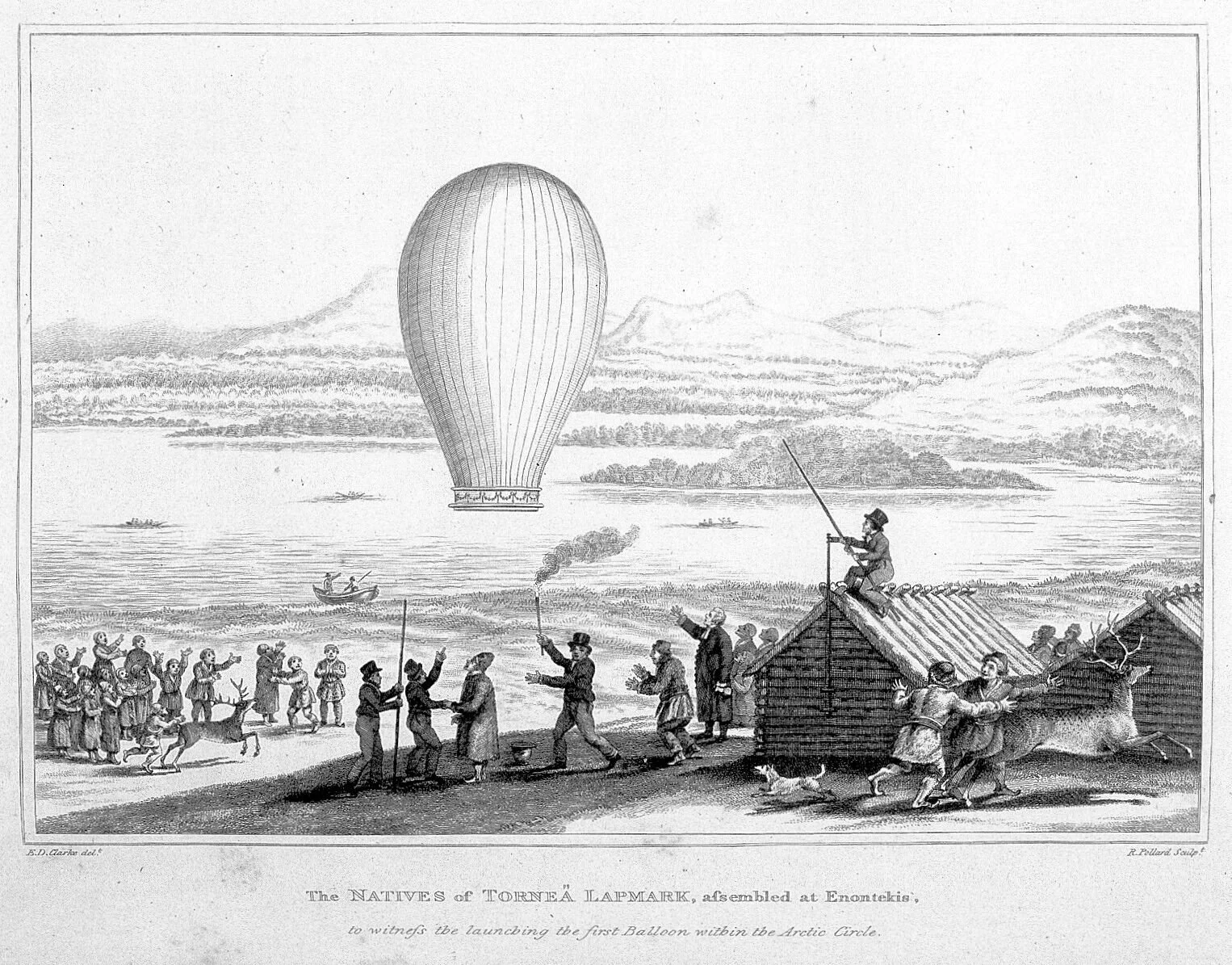

The Natives of Tornea Lapmark, assembled at Enontekis to witness the launching of the first Balloon within the Arctic Circle. Edward D. Clarke (artist). Robert Pollard (engraver). 1819. Illustration in Edward Daniel Clarke, Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. Wellcome Collection.

In the summer of 1799, the English traveller Edward Daniel Clarke (1769-1822) and his student John Marten Cripps (1780-1853) travelled through northern Scandinavia to Sápmi. Clarke was eager to encounter and observe the Sámi people and particularly reindeer-herding Sámi. Clarke used local clergymen, whose services the Sámi were obliged to visit, as informants regarding the whereabouts of the Sámi. Clarke also developed a spectacular plan to attract the Sámi. Writing from Torneå to a friend at Cambridge, he explained that he would ‘launch a balloon at the capital of Torneå Lapmark; in order to attract the natives together’. A couple of weeks later Clarke, via the clergyman Eric Grape, sent out notices advertising the launch. When it was eventually launched, the balloon which was described as being ‘seventeen feet in height, and nearly fifty in circumference; and being all of white satin-paper, set off with scarlet hangings’, attracted a large crowd.

There are no preserved Sámi accounts of what the many Sámi individuals who encountered Clarke and his balloon in 1799 thought of him and his travel companions. This includes the lack of Sámi quotation, and a lack of conscious effort to convey a Sámi voice, in Clarke’s own published work. Colonial texts can nevertheless provide glimpses of Indigenous presence and agency and it is possible to excavate ‘Indigenous countersigns’. These were moments during which colonial narratives were challenged by Indigenous people through for example laughter, indifferent silence, indignation, noisy ridicule, sharp rebuke.

Clarke’s eagerly anticipated balloon display did not go as planned and includes examples of “countersigns”. A crowd had gathered but the launch of the balloon was delayed due to strong winds. The winds also tore the balloon while it was inflating and it fell to the ground. Clarke had to repair the balloon and relaunch it in the evening. The Sámi audience became increasingly impatient and believed that he ‘intended to make dupes of them’. Clarke wrote that they became ‘riotous’ and that some left. The second launch attempt succeeded but the Sámi did not seem to appreciate the display. The engraving, by Robert Pollard and published in Clarke’s travelogue, shows Clarke and Grape at centre stage while the Sámi scatter in different directions. The balloon frightened the reindeer and, according to Clarke, the Sámi misconstrued it as product of ‘magical art’ rather than the great scientific project Clarke held it up to be. He noted that the balloon produced ‘rather unease, than pleasure’ and that the Sámi were ‘dismay[ed]’.

Clarke’s delay and lack of success with the balloon is also twinned with his emphasis on the Sámi’s alleged backwardness and superstition. The balloon was not only a medium for attracting the attention of local inhabitants but also a means of provoking reactions. Clarke wanted to gauge whether the balloon prompted a scientific curiosity. Although some Sámi stayed to witness the balloon, others had had enough and left before his spectacle took place. Writing to his mother, the day after the launch, Clarke did not mention the mishaps and instead misconstrued it as a success: ‘Yesterday I launched a balloon…which I had made to attract the natives. You may guess their astonishment, when they saw it rise.’ The balloon incident later featured in several reviews of Clarke’s travelogue. However, rather than being presented as a pioneering scientific display it was depicted either as a comical episode or as one that had scared the Sámi.

Essay by Linda Andersson Burnett